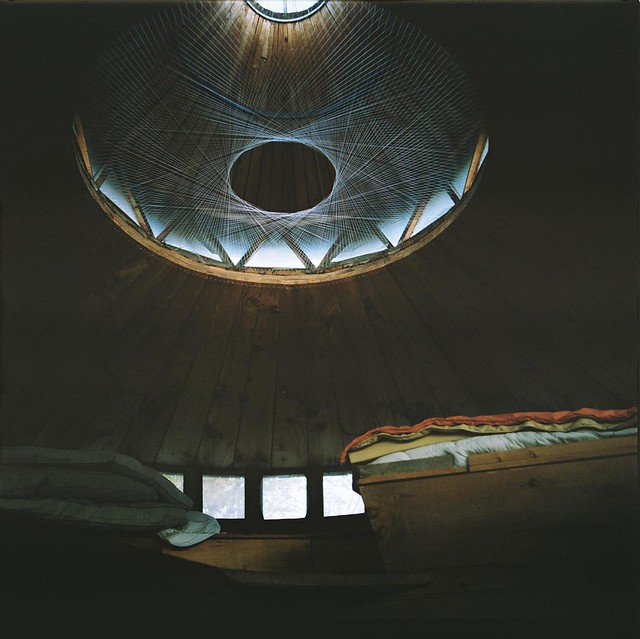

“Looks like a broken window you’ve got there.” I repeat at an awkward volume for this still wilderness, pointing my words at the leathery hand cupped at Bill Coperthwaite’s ear. At eighty-four, his hearing is going. We are standing in his guest yurt, a one-and-a-half story stack of his first yurt design (which is now the smaller, inner story) and the later, larger addition which wraps concentrically around it. The western side of the room is constellated with a small blast of glass bits. “Ah.” Bill responds.

Opening the door slowly, as to avoid disturbing the nesting hornets that live by the hinges, Bill steps backwards out of the yurt (his preferred method, which keeps one from banging their forehead on the low doorways) into the bright sun. He pads through the grass to inspect the broken window, and happens upon a dead grouse.

“Ah”, he repeats, musing on the development. When he is lost in thought like this, he absentmindedly knocks his false teeth around in his mouth. It sounds like a kid with a jawbreaker. We stand in silence for a moment or two, both staring at the poor thing. And then, with one word, “Dinner!”, he scoops up the dead bird by the feet and carries it, head loosely swinging, down the footpath to his yurt’s kitchen, which is a marvel in and of itself. Darkly patinated, wide-plank countertops hand carved to match the curving walls, his ingenious water-tank made from a cylinder of birch bark, and a filthy glass pitcher of furiously fermenting, neon-pink liquid Bill lovingly dubs “hooch”, a concoction made up of Welch’s grape juice concentrate and a few hibiscus tea bags. It sounds like an inexhaustible bowl of Rice Krispies.

In 1973 the ocean front of Northern Maine was a different place. Clearcut, infertile, and hours from even the most minor convenience, the land was not widely considered desirable. At the time, Bill heard the logging companies were offering land in Machiasport at six dollars per acre. He bought 300, which seemed outlandish and selfish to him then, but now, as the waterfront condo developments hedge in his boundary lines, a move he thanks himself for. Since that day, he’s spent the better part of forty years playing around with house design, specifically yurt design. His simple structures are efficient and nicely suited to the climate here. Being essentially a series of stacked circles, heat circulates easily during winter, and the long, low rooflines keep the sun from penetrating deep into the rooms during summer. And though the walls are thin pine boards, he burns very little wood during the winter, even without sealing his windows. When I ask about the total lack of weatherproofing, he tilts his head in curiosity and smiles a little. “What do you mean? I need to breathe. The fire needs to breathe. If I burned more wood, than I guess I’d worry about it. Why is everybody so scared of a little air?”

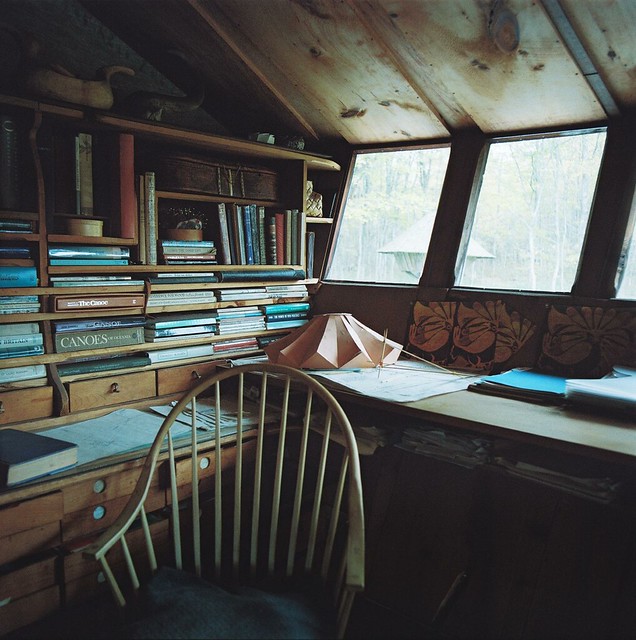

It’s not the yurt that specifically interests Bill. Having mastered that one form allows him to use it as a template, but he is an ecologist before he is a designer. It is clear, after spending a bit of time by his side, that his interest is in the materials; how to most comfortably and enjoyably articulate space with a minimum of highly valued materials. Emphasis here on the value of materials, hard-won by slow and labored work. Bill wastes very little material in his work, as would anyone if they had to pull tied flotillas of lumber behind their canoe, many miles from the sawmill to the work site. And while his lifestyle is admittedly at the boundaries of what most people would accept as comfortable, he has lived out an incredible experiment, whittling away every bit of excess from his life and his building methods. Almost nothing is wasted. Even his broken tools, having worn themselves to relative uselessness, are thoughtfully repurposed to new ends.

We spent a couple of days working on his newest design, a single-room yurt with a bizarrely folded roof design; the ceiling is plywood tortured into compound curves. The walls are lapstrake cedar, and it requires two people to clinch the nails through the overlaps in the boards- I backed up and bent the nails into a semi-circle while he drove them through the walls. Bill spent most of the time talking about the merits of efficiency that an electric screwgun would have in this situation. We finished work and gathered up some food for dinner, and Bill chatted aimlessly while plucking the dead grouse free of its feathers. Dinner was two or three times as much food as we should have eaten, grouse and sauteed vegetables. Out of politeness, (and against my better judgement), I shared the meat with him, which was fantastic; winey and tender. After a day of carpentry in the brisk October wind and light, we ate in the warm wooden room without much talk. The hooch’s dense crackling padded the quiet of the room.

During the long drive home, it was not any conversation or particular building that stood out most in my memory, but his sinewy and ancient hands. They were transfixing. Constantly mobile. Palms like hide. The back of the hand soft, smooth, mottled and almost translucently thin. Old but sure. On Wednesday morning, our pant legs damp and heavy from the walk through the tall wild grasses, we set to work on his new yurt, and he fumbled the first nail. Searching through the dirt and leaves, he grumbled “Dropped my first nail. Might as well go back to bed.”

We worked until lunch, when I had to leave, and after eating I packed my bag in the stream of brilliant sunlight that shot down through the the aligned doorways of each of the yurt’s floors. When Bill thanked me for visiting, and climbed—brightly backlit—into the loft for his afternoon nap, it looked as though he was tugging his rangy body into the sky.