17.9.15

Shutter problems.

Sigh.

Both of my dear film cameras, a Leica M6TTL and Hasselblad 500C/M, seem to be experiencing some weird underexposed lines in their exposures.

From the botched rolls:

Both of my dear film cameras, a Leica M6TTL and Hasselblad 500C/M, seem to be experiencing some weird underexposed lines in their exposures.

From the botched rolls:

23.6.15

17.3.15

1.2.15

Enzo Mari/Sammie Warren.

An unexpected gift from this past summer: an exquisitely crafted table and chair set from our dearest friend Sammie, based on an Enzo Mari design from the latter's Autoprogettazione. A reminder that the charming thing about perfectionists is that they never recognize themselves as such.

23.10.14

9.10.14

Geospectrography OR The color where you stand.

"I'm not going to claim it's a highly respected academic theory, but it's certainly a widely held one."

With these words, my dear friend Ginny reaches over our shared mountain of fries and sips from an immense glass of dark beer, a glass maybe three times the circumference of her fine, pale wrist. We often meet for lunch in this heavily lacquered pub in central Maine, where we can sit for hours in the assurance that the two of us are the lunch rush, and no one is waiting for our table. We talk about art, tragedy, annoying politics. Ginny, (formerly my college professor in art history and one of my favorite dinner companions), was describing the popular notion within art history that some paintings are dated by cross-referencing colors within the painting with knowledge about when a painter lived where. At the time, she cited Van Gogh's paintings made in Paris as compared to those paintings made in the south of France in Arles. "The colors are completely different! It's obvious." She declared.

Evidently, if and when an unknown painting pops up, a historian can often judge where (and consequently, narrow down the more importantwhen) a painting was made simply by observing the "color of the light" reproduced within it. Not too long after this phenomenon occurred to the cultural subconscious, it was taken up and championed by the then-scandalized Impressionist painters, who claimed-- with varying degrees of credence-- to reproduce the colors of nature exactly as their eyes perceived them.

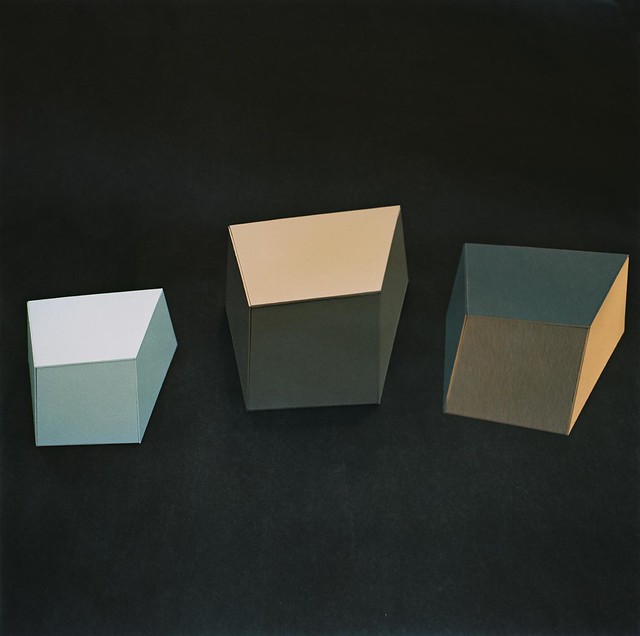

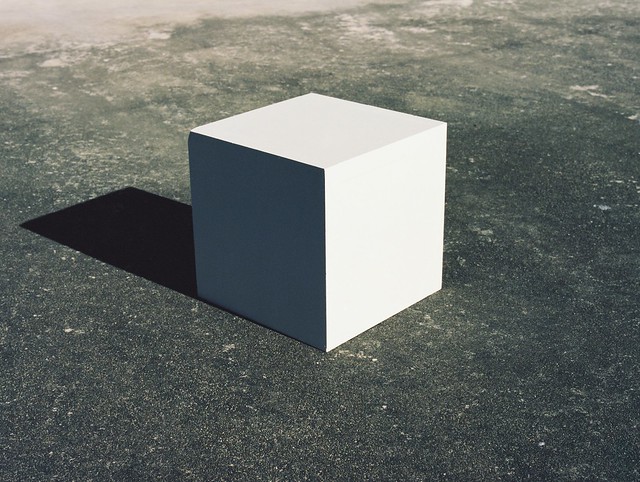

It was a fascinating notion to me. It isn't so hard to notice the color shift in morning light vs. evening light; one only needs 12 hours to make a decent observation. The photo below illustrates it plainly enough, three exposures of the same white paper sculpture at 6 a.m., noon, and 6 p.m.

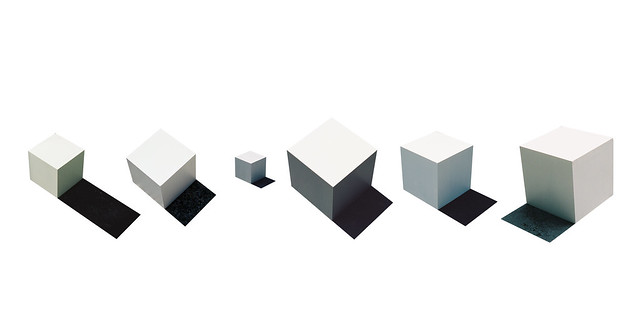

But this concept was larger than that. It took the color shift created by the angle of incidence in sunlight over the course of a day and inflated it. To a global scale. Almost a planetary scale, since, at its essence, the idea is dealing with the earth as a giant sphere on which light falls asymmetrically.

It was an idea worth investigating, and so, well....actions were taken. And this past summer, seven packages were sent around the globe to seven exemplary photographers.

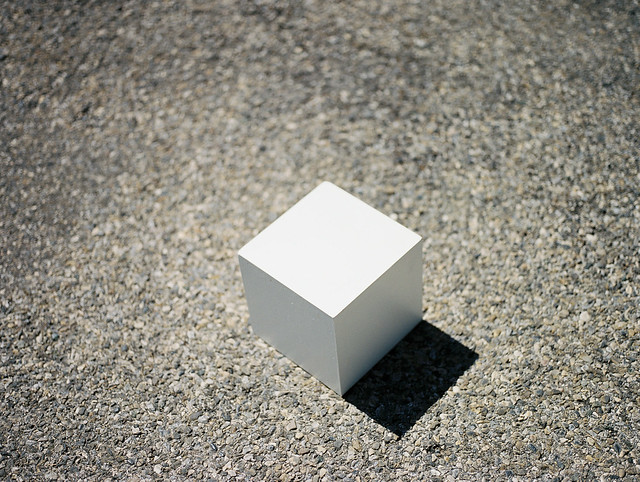

In each box was an eight inch wooden cube painted with white primer, a roll of Kodak Portra film, and a sheet of instructions. These were sent to Portland east and Portland west in the United States. To NYC. To Christchurch, New Zealand. To southern France, Mexico City, and Bergen, Norway.

The guidelines were pretty straightforward;

Photograph the cube with the included film, at the same time (noon) and on the same day(August 3rd), with an aperture of f/22 and a shutter speed of 1/500 of a second.

Pick a neutral environment. Avoid color casts from your surroundings.

Most of all, make sure the sky is completely clear; wait a day or two, or shoot a day early if necessary.

The shift in light from morning to evening can be experienced on a bodily scale. It's part-and-parcel with circadian rhythms. But the geographic differences in light could only be assessed collaboratively.

All of these images were shot on the same settings, under the same clear sky, as close together in time as life would allow, (taking into account "little" details like time zones, of course).

They were processed in the same chemicals, scanned on the same machine with zero color balancing, and remained unedited. The one thing we didn't take into account was using the exact same lens. That's a project for another time. But that fact--the lens variation-- is a fault in the equation. It bugs me that the discrepancy exists, because it opens the door to doubt.

But look at it this way. At some point, the human race will follow through with a conclusive spectrographic test and discover this phenomenon to be real or not. In the meantime, I present you with the results of a fairly rigorous and involved experiment, an attempt to suss out whether all those art historians are latching on to some profound truth about our world. One narrative dismisses something potentially wondrous because of a missing ingredient. The other gets to enjoy gawking, awestruck by the profound, subtle and unsung workings of a rich and delicate planet.

I'm cheerleading for the latter.

So. Enjoy this, a hard-won photographic overlay of six completely identical "white" cubes, the biggest difference among them being their geographic distance from one another when shot.

Many thanks to the incredible and inspiring photographers that made this possible. I love them all. Only the top image was shot by me.

Brian Ferry

Mary Gaudin

Marion Berrin

Stephanie Congdon Barnes

RTS & MAV

Jonas Romo

Thanks guys.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)